How to Balance Ecological, Social, and Economic Uses of Forests to Sustain Life on Earth

By Norton Siano Ribeiro de Freitas

"Hill Hurst afforded the serenest period for learning the effects of the change of seasons I had ever known…"

N.S.R.F

I try to practice as an environmental scientist and economist today, and I find it very challenging. The journey to come to this position stretches back to Wellesley, New England when I was just getting started in College. I sometimes did my studying at Hill Hurst and, I was thrilled to see the change of seasons, leaving the forest floor so studded with fallen leaves that I was hardly aware in Brazil (my native country), forest trees remain mostly green around the year and minded how forests and the atmosphere interact more than anytime since.

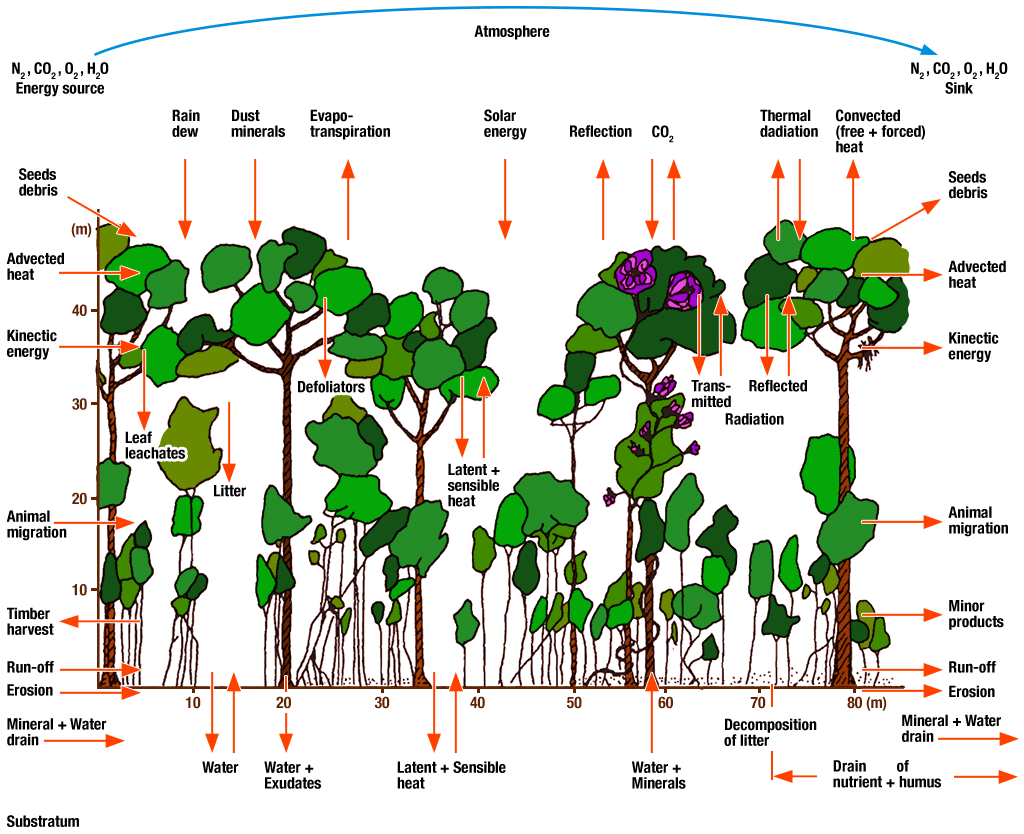

Throughout my career, I took a keen interest to measure the output of goods and services from forest ecosystems than to leave it to silent reflection. But, if you turn, for instance, to the schematic model of a tropical rainforest (1), you find that accounting for the interaction of plants with the atmosphere, is an arduous project. The atmosphere (a mass of gases, charged particles, and suspended solid and liquid matter) is the environment in which we spend our whole life. It regulates the exchange of carbon dioxide, water vapor and biomass production. It is therefore the sustainer of life, man’s most vital resource.

(1) Profile diagram of a tropical rain forest showing some of the movements of nutrients and energy into and out of the ecosystem (Adapted from Tropical Forest Ecosystem: A State of The Knowledge Report. UNESCO Natural Resources Research n.14, 1978).

Major gas components of the atmosphere are consumed and reenter the atmosphere after interacting with organisms, products of their life activity, water and mineral substances, as shown in the drawing at the top. Energies in the infra-red, ultraviolet, and x-ray parts of the spectrum interact continuously with the atmosphere producing a variety of phenomena resulting from energy transfer which analysis would be difficult without the advances that have been made in infrared physics and laser spectroscopy in the past decades to investigate plant diseases as well as the characterization and identification of trace gases - both opening up undreamt-of vistas.

I therefore spent considerable time working at postdoc level, side by side with able and thoughtful experts of ecosystem research to understand the mechanisms controlling the movement of gases, energy and mineral substances between the soil, and between the forest and the atmosphere above the forest. As time went on, those associations helped to gain research experience and also to have access to laboratory facilities in such diverse areas as environmental physics and isotope geochemistry, that were needed for synthesizing the interactions and feedbacks among sensitive ecosystems that generate and maintain plant species biodiversity, as well as those that can result in its reduction in the face of external perturbations. Many of my associations involved collaboration and cooperation with the public and private sectors. In these exchanges, I sought out poorly understood problems within the overwhelmingly complex Atlantic Rainforest, particularly those that have consequences in a broader societal context, such as aligning the public and private benefits of forests, for balancing the dynamic between conservation and conversion.

Markets reward forest owners for converting forests to market products, but fail to award them for conserving forests to provide ecosystem services, even when the latter contribute much more value to society than the former. We notice in Brazil forests are very fragmented. As these forests are continually molded and transformed by land use due to heterogeneous socioeconomic activities, regions compete with dynamic patterns of economic development. The rising demand and competition for land and other resources has an impact on prices and is exacerbated by climate change. This makes it much more difficult to manage an entire landscape for ecosystem functions. The problem is that the land owner captures the benefits from timber harvest and from conversion, but shares the public good benefits of conservation with society.

Since such public goods are inherently non excludable, markets provide no incentive to provide them. Much more relevant is rent generated from parcelization. In many cases the land owner makes significant profit plainly by breaking up the land and selling it. This means that forests may be converted even when the value of clean water, clean air and biodiversity completely outweight the benefits of conversion. As the marginal costs of damage to ecosystem services rise with their increasing scarcity, solving this problem becomes very urgent.

It amazes me that in Brazil, where the devastation of large blocks of forests would require a more joined up, collective approach to redefine the use of forests beyond their economic value, the necessity to incorporate a new understanding of ecologically sustainable forest management and recreation is not yet widely recognized. And this, of course, is the central challenge of the 21st century – how can we ensure that, policy solutions should do more than merely shift away from old-growth logging to ecological restoration, the creation of rural job opportunities, shorter timeframes for crafting forest plans, protection of wildlife and water resources, and responding to climate change impacts? Forests play a key role in generating ecosystem services essential for life, which need to be monitored and evaluated in the light of societal expectations, not just economic ones.

Back in 2016, I followed the Olympic Games in Rio and quite apart from the contradictions inherent to hosting colossal sporting events I was impressed by the opening ceremony – a celebration of peace and humanism that did not shy away from the big question today: Climate Change. A film showing that glaciers are disappearing, the ice-caps are melting and the weather is becoming more extreme called into question humanity’s continued survival on the planet. And, in order to stimulate the debate about how practical steps could be taken to move towards a low-carbon future, athletes drawn from all parts of the world planted native seeds from the Atlantic Rainforest. The novelty of the idea to plant a forest awarded a very high grade to the event. For, in planting the Athlete´s Forest in Rio, “Olympians” provided inspiration to find ways to adapt to climate change and so ensure that such urgent challenge would not be left until later.

Athletes like plants have various degrees of competitive strength and stress tolerance that contribute to their success under specific conditions. Their strength and perseverance is of such importance that I wonder if the collaboration they engaged will inspire Brazil to eagerly embrace the advantages in pursuing a sustainable future, announced at the Earth Summit, which was also held in Rio - the meeting that agreed the Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biodiversity. But, leaving that aside, in analyzing what can be learned from linking the “Olympians” with the mega science presented an argument for writing this essay, as the race in which scientists and economists should all be engaged now is to sustain life on earth.

There are many reasons for this. First, man is part of the global environment and therefore cannot achieve and maintain health and well-being if conditions are not suitable for environmental health. There is also the further significant fact that changes in gas concentrations and aerosols on the radiation balance of the atmosphere should be fully understood in view of man’s ability to modify them. Thus we have to draw on the knowledge that plants change the composition of the air and the air changes the physical and chemical composition of plants. Plant species maintain the gaseous composition of the atmosphere stable and detoxify absorbed pollutants.

Further, we have to admit that the need to consider human accidents, economic impacts and social disturbances caused by weather is pressing within industrial and government spheres. Therefore, there is a specific interest to know the consequences of man’s activities on climate before the consequences become irreversible and also because of the great economic importance of being able to make useful seasonable predictions. The origin of this interest was reflected by Hippocrates, the Greek physician of the Age of Pericles, who thought hard about the need for man to deepen the understanding of rapidly changing weather patterns in order to be guarded during the greatest changes of the seasons, which translates into today´s collective consciousness of the damages of climate change. Is there not an opportunity and challenge today for Brazil and other rainforest nations to make a difference much more quickly to deal with the increasingly severe and frequent changes that Hippocrates observed so incisively?

Having explored the dynamics of land use to assist Brazilian farmers to keep ecologically productive land forested, the emphasis in my practice rests more on facts than on hypotheses. In short, on developing indicators that lead to managing unprotected landscapes for maximum ecosystem services yield to maintain natural capital (essential for environmental sustainability), and solve many conservation problems through replanting areas from which forest cover is absent to “working forests”, where a wide range of forest-related activities can coexist.

Natural capital stock produces a flow of services and inputs into the productive processes. Any level of flow that is associated with a reduction in the capital stock is unsustainable. However, declining natural capital may be compensated by another type of capital. “Working Forests” - which are not natural ecological systems, but can provide revenue while generating ecosystem services -, represent a fortunate confluence of scientific understanding and technical capability, increasing sufficiently to compensate for this decline; they are directed to induce land owners to plan their properties in a way to minimize the dangers of severe storms, erosion and to control pollution.

Understanding how much of the landscape can be allocated to working forests should be evaluated on a property-by-property basis and user needs within the context of what they are being asked to do. Since not every parcel of land can produce the same ecosystem goods or services, it is common sense to structure farms to capture multiple services in various combinations, and in turn propose mechanisms through which the beneficiaries of these ecosystem services can finance their provision. This requires that adjacent land owners create spatially contiguous working forests for the delivery of ecosystem services from farmland across their common borders to protect endangered species and biodiversity by reuniting fragmented habitat to minimize negative impacts and contribute towards the sustainability of land systems and their use. So, in planning to achieve resilient landscapes, one should really understand the ecosystem responses stemming from land use conversion as having important influences on land use, environmental quality, biodiversity, biogeochemical and hydrological cycles, including measures to quantify such responses and relating these responses to the climatic effects they arouse. Thus balance ecological benefits, social uses and economic value from forests to sustain life in earth.